Causes are the things that happen in our system, or to our system, that can lead to an unplanned event occurring. They can generally be categorised into one or more of the following categories:

So far in this series we’ve discussed the basics of why we have Hazard Logs and how to write a Well-Written Hazard. In this article I will talk more about Causes and Consequences, and how to do a risk assessment if needed.

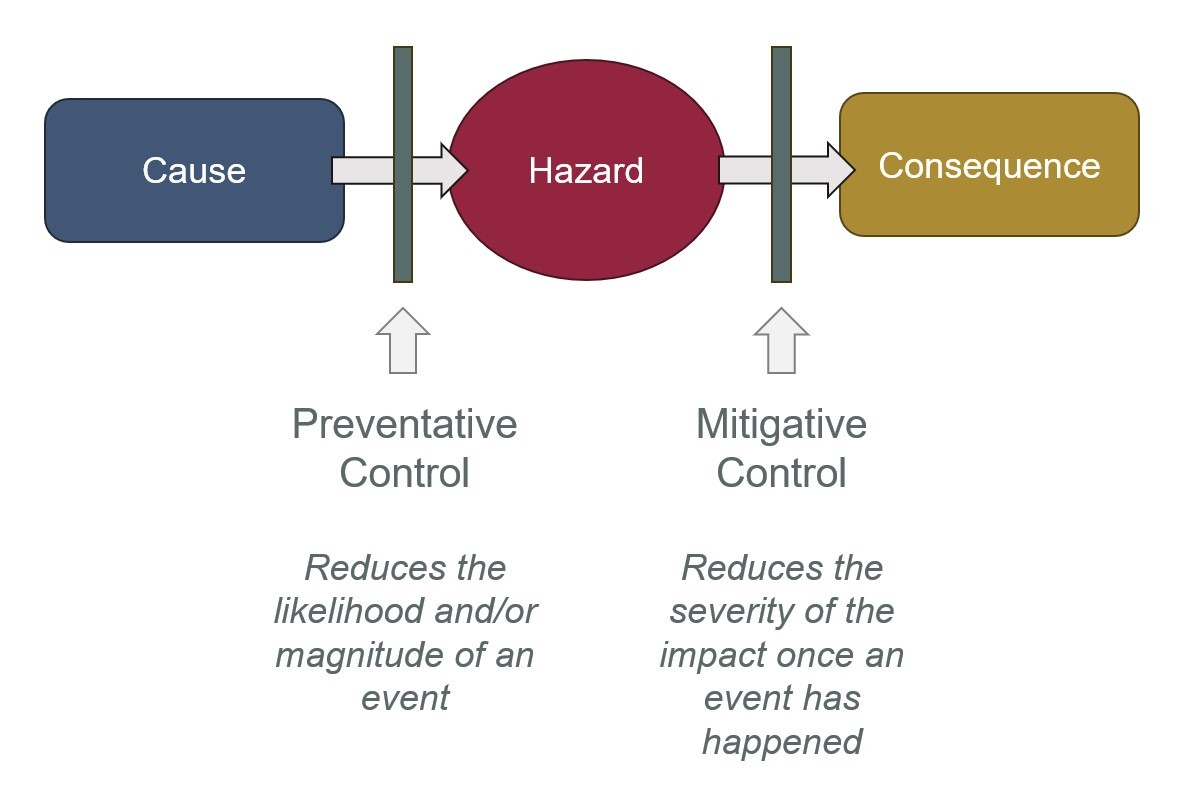

In Part #4 I will discuss Controls in more detail, but I will provide a brief summary here as it will help with some of the concepts discussed below.

Although quite simple, bearing these concepts in mind will help you to write causes and consequences. Remember an efficient Hazard Log is management tool, so when identifying Causes and Consequences we’re really identifying things that can be managed by a Control.

Causes are the things that happen in our system, or to our system, that can lead to an unplanned event occurring. They can generally be categorised into one or more of the following categories:

When identifying causes try and keep in mind that the real purpose is to try and identify those Preventative Controls that can limit the likelihood or magnitude of the hazard. Particularly with External Influences, don’t get carried away with trying to capture things where you have little or no control such as major weather or ‘force majeure’ events.

In my previous article I gave the example that ‘Strong Winds’ would not be a hazard on its own but could be the unplanned event that could lead to a collapse of a temporary structure. But would we consider strong winds a cause in their own right? It really depends on the context and the scenario.

In the example of the temporary structure, we may have designed it to withstand 30kph winds during installation. So a hazard cause could be phrased as strong winds over 30kph during the lifting operations.

When describing the cause make it sufficiently specific that the incident sequence makes sense, and then it also becomes easy to identify potential Preventative Controls (i.e. check the weather forecast before starting work; install an anemometer with an audio alarm; have plans to secure loose equipment; etc.)

One of the basic premises of risk assessment is the concept of Reasonably Foreseeable. Causes should be things that are realistic, reasonable and sensible, with a fair chance of happening in the selected timescales. In the previous example, we would be happy that a strong gust of wind could be a reasonably foreseeable external influence.

However, unless you are directly under the approach path to an airport, we wouldn’t expect to put ‘plane falls from the sky’ as a cause of a structural collapse. Yes, it could theoretically happen, but the likelihood is so low we would not consider it to be reasonably foreseeable.

It is also a common mistake to have multiple events to create a cause such as – “what if A happened, and then what if B happened, and then what if C happened?” An event described like this, where you’re looking effectively at three consecutive failures would not pass the test of reasonably foreseeable. A lawyer once told me "you only get one 'and if' in court", so I try to stick with that.

Another consideration when identifying causes is the type of person initiating the event. You’re typically looking at an employee, customer, or member of the public going about their everyday business. Don’t try and develop causal scenarios based on malicious intent trying to overcome reasonable security precautions. If your scenario is starting to look like a scene from a James Bond movie, then you’re probably overdoing it.

When identifying the consequences of a hazard, try and cover a range of possible impacts such that mitigative controls can be assessed for different potential incident scenarios. What I mean here is that different consequence events may require different responses, so by making sure you identify the reasonably foreseeable events, you can assess all the relevant mitigative controls.

I find it’s good practice to describe the event and assign a likely accident severity at the same time so that someone reading the Hazard Log later can understand your thinking. E.g. “person struck by door, minor injury” or “high speed derailment, multiple fatalities”.

Consequences may result in many types of harm, some of which may not result in an immediate injury, but could lead to an indirect safety risk. For example, delays on a railway can lead to overcrowding and late running, which in turn can be a contributing factor to other safety events.

We may therefore capture ‘operational delays’ as a consequence event but don’t necessarily need to assign a level of severity to it, but just want to understand the impact so that we can be confident we have appropriate controls in place to minimise delays and recover the service.

Some clients may require that a risk assessment be undertaken in accordance with their enterprise risk matrix to inform their risk tolerability and risk acceptance process.

When doing this the first step is to identify which one of the multiple incident scenarios should be used to assess the risk. The typical approach for this is to use the principle of realistic worst case. In theory, all accidents could result in a fatality, but often it’s extremely unlikely. This is usually a judgment-based decision by a competent professional or group of professionals.

Example: A paper cut could in theory become infected and result in a serious illness or death, but we know that’s not really going to happen in most cases. The realistic worst case for a paper cut would be a first-aid injury with a sticking plaster applied. A realistic worst case for a fall on stairs may be a major injury, for a high speed derailment it could be multiple fatalities.

Once the realistic worst case has been determined, the likelihood is assessed based upon that consequence occurring. It’s important to not assess the likelihood of the hazard occurring, but the likelihood of the selected consequence occurring. This is a common mistake that regularly results in risks being assessed much higher than they actually are.

If a different consequence is selected, don’t worry too much as the corresponding change in likelihood will generally result in the same risk ranking.

Remember risk assessments in Hazard Logs are to support the clients risk acceptance process, they do not form the basis of your SFAIRP argument.

So here are my five takeaways, get these right and you won’t be far off the mark when it comes to writing causes, consequences, and risk assessments:

Causes and consequences should be reasonable and realistic and ultimately written to inform the potential controls. Risk assessments are a nice to have and inform clients risk acceptance process.

#ARCHArtifex #Assurance #HazardLog

This is part #3 of a series of articles in this series, so some of your questions will be answered in more detail later. If you have any questions, you’d like answered in these then send me message.

Hazard Log #1 – Back to Basics

Hazard Log #2 – The Well-Written Hazard

Hazard Log #3 – Causes and Consequences (This Article)

Hazard Log #4 – The Importance of Effective Controls

Hazard Log #5 – Managing Closure

Hazard Log #6 – Assumptions, Dependencies, & Constraints

Hazard Log #7 – General Guidance